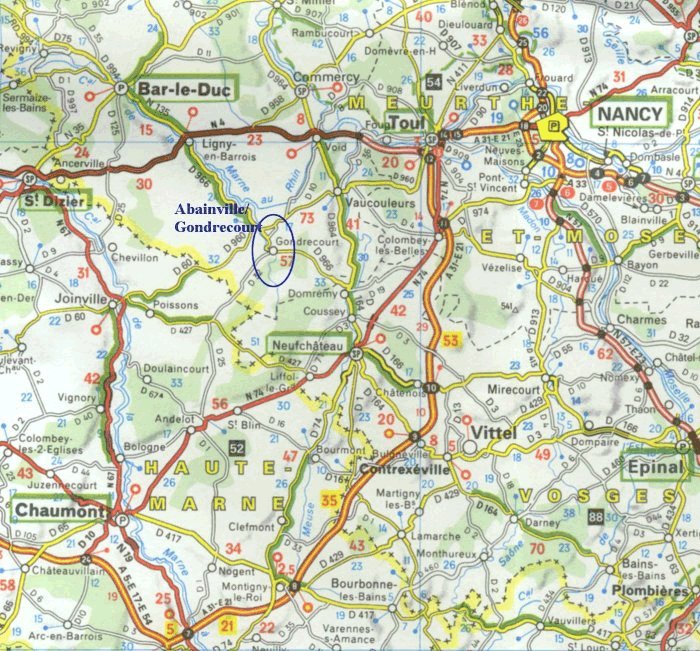

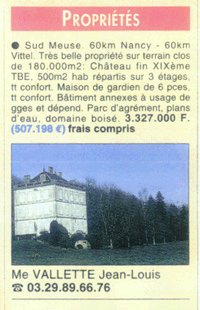

South Meuse. 60km from Nancy and Vittel. Beautiful walled estate of 45 acres: manor dating to end of XIXth century with 1500 sq. ft. on each of three stories including all amenities. 4/5 bedroom lodge (custodial gate house) with all amenities. Miscellaneous out buildings converted to garage and storage. Gardens, ponds and woods. 3,327,000 francs or 507,198 Euros (about $500,000 US in 1999) including all closings costs. Contact Jean-Louis Vallette, notary."